Slow COMT: The Definitive Clinical Guide for Testing and Optimization

Slow COMT is a biochemical variant that can profoundly shape mood, stress tolerance, and even how you respond to vitamins or caffeine. If you’ve ever felt “tired but wired”— exhausted in body yet racing in mind—or found that B vitamins and coffee make you jittery and anxious, the slow COMT gene variant is very likely the hidden key.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll show you clearly what COMT is (and the famous Val158Met polymorphism), how to identify a slow variant in your genetic data, and, most importantly, how to optimize your lifestyle and supplementation to feel better.

We’ll also highlight what to avoid (yes, there are “healthy” supplements that can backfire for slow COMT-ers). By the end, you’ll have a reasonably clear plan for managing a slow COMT.

Slow COMT variants often leave people feeling overstimulated yet fatigued – the classic “wired but tired” state. Learning how to read these genetic clues and adjust your lifestyle can bring profound relief:

What Is COMT? (And Why Val158Met Matters)

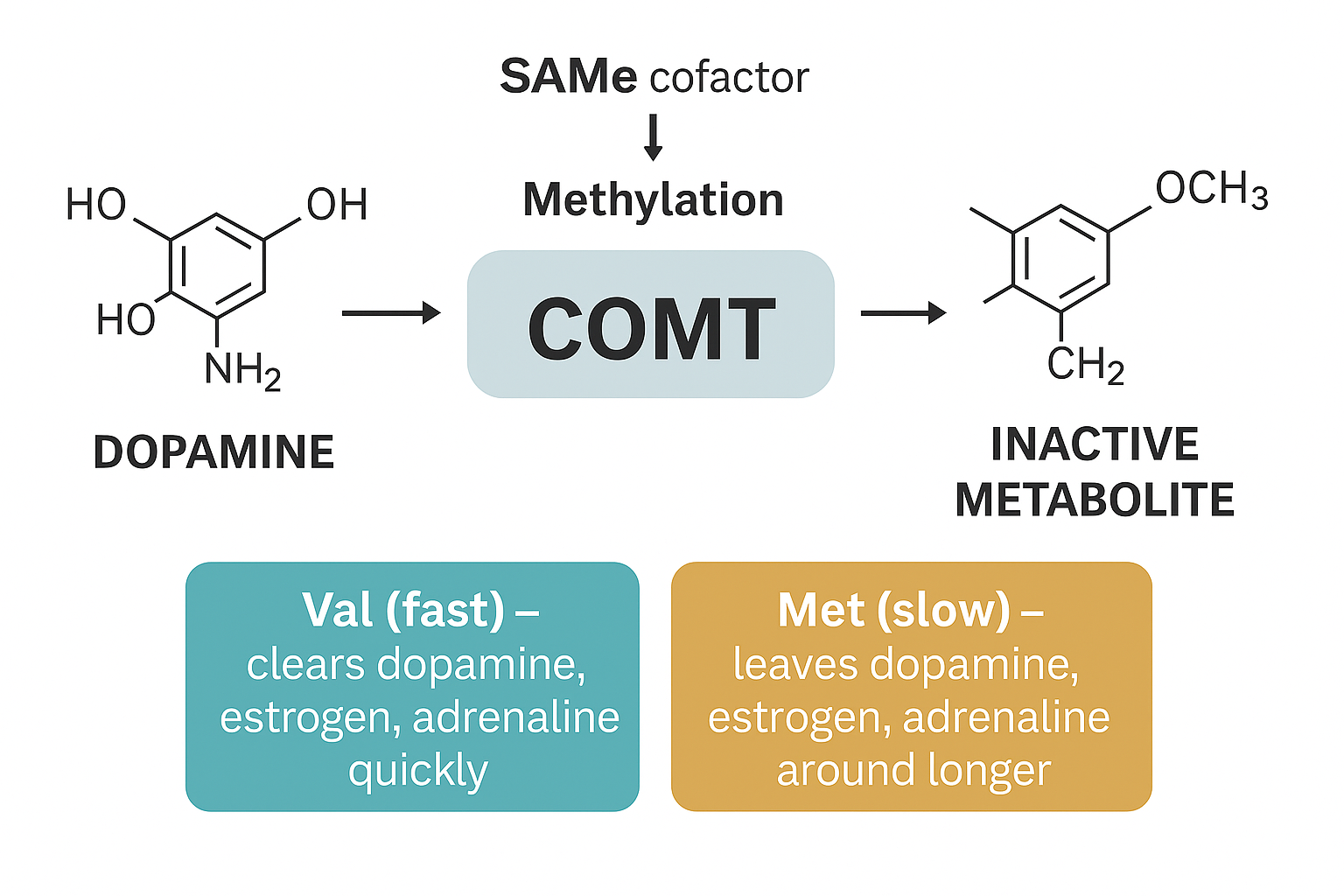

COMT stands for catechol-O-methyltransferase, an enzyme that acts as one of the body’s primary breaks for certain stimulatory chemicals.

In simple terms, COMT’s job is to break down and clear out catecholamines—a family of activating molecules that includes dopamine, epinephrine (adrenaline), and norepinephrine (noradrenaline)—as well as certain forms of estrogen.

When COMT is working efficiently, it helps your nervous system return to baseline after stress or excitement by methylating (deactivating) these neurotransmitters and hormones for elimination.

Think of COMT as a biochemical break that calms things down in your prefrontal cortex (the “thinking” part of your brain).

One particular genetic variant of COMT has outsized influence: the rs4680 polymorphism, better known as Val158Met. This SNP (single-nucleotide polymorphism) has a huge impact on the speed of your COMT enzyme:

Val/Val (G/G genotype): The so-called “fast COMT” version—leads to a higher-functioning enzyme that clears dopamine and other catecholamines quickly. Fast COMT people tend to have lower baseline dopamine levels in the brain (which can mean more trouble with focus or motivation) but also lower estrogen metabolites in the body.

Met/Met (A/A genotype): The classic “slow COMT”—produces an enzyme that is 3–4 times slower at its job. Consequently, dopamine, adrenaline, and estrogen levels run higher at baseline because they aren’t broken down as fast. This A/A genotype is often the culprit behind the “overloaded” feelings we’ll describe soon. Roughly 20% of people carry the Met/Met slow variant.

Val/Met (A/G genotype): A “medium” or intermediate COMT—falls in between, with moderately reduced enzyme speed. These individuals can have milder versions of the slow-COMT pattern, depending on other factors.

Why does Val158Met matter? Because it can fundamentally tilt your neurochemical balance. A slow COMT (Met/Met or A/A) means higher tonic dopamine levels – which sounds like it could be a good thing for mood and cognition, until it tilts into overstimulation.

Higher dopamine and norepinephrine can translate to anxiety, racing thoughts, and insomnia.

While higher unmetabolized estrogen (especially catechol-estrogens like 4-OH estrogen) may raise issues like PMS symptoms or increased breast cancer risk.

By contrast, a fast COMT (Val/Val) can mean low dopamine (potentially brain fog, low motivation, or susceptibility to ADD/ADHD traits, but is less likely to struggle with estrogen overload. Neither is inherently “bad”—they each have pros and cons—but if you have the slow variant, you’ll need a tailored approach to keep those pros (like better attention to detail and memory) without the cons (anxiety and sleep trouble).

Slow COMT vs Fast COMT

Why a “Slow COMT” Can Cause So Many Symptoms

Yes, it’s understandably surprising that a single gene variant could cause such a wide array of symptoms, but COMT simply does a lot of stuff.

Slow COMT function means your ability to clear stress and stimulation is delayed.

In clinical practice, many people with unexplained anxiety, insomnia, or mystery “overstimulation” symptoms turn out to have a slow COMT variant. COMT variants are among the most impactful common genes we see at MTHFRSolve, even more than MTHFR, precisely because the symptoms are so pervasive.

When COMT is slow, activating molecules linger longer in your brain and body than they should.

That means every stressful event, every cup of coffee, every dose of B12, and every hormonal fluctuation can feel more intense and last longer than expected. Over time, this creates a pattern of chronic stimulation followed by eventual burnout. The nervous system never fully “resets” before the next wave hits. It’s a bit like a sink where the drain is partially clogged: even a normal flow of water (stress or stimulants) eventually overflows because it can’t drain out fast enough. The result is a gradually building constellation of symptoms that can span mental, emotional, and physical domains.

Let’s look at those symptoms:

Symptoms and Clinical Patterns of Slow COMT

People with slow COMT often experience a distinct cluster of symptoms that may initially appear contradictory.

It’s common to feel simultaneously overstimulated and exhausted, or to react paradoxically to things (like getting anxious from a calming supplement or sleepy from a stimulant). Below, we break down common Slow COMT symptoms into categories, based on clinical observations and patient reports. See if several of these resonate:

Mental & Cognitive Symptoms

“Wired but tired” brain: Feeling mentally overstimulated even when physically drained. You might have racing thoughts (especially when you try to relax) and persistent brain fog that actually worsens under pressure or multitasking.

Focus paradoxes: Difficulty concentrating on mundane tasks or in quiet settings, yet sometimes experiencing hyperfocus during a crisis or under last-minute deadlines. This paradox can confuse practitioners—“is it ADHD (trouble focusing) or OCD (hyperfocus on certain things)”!? In a Slow COMT individual, it can be both, depending on the context.

Overanalysis and obsessiveness: A tendency to overthink or ruminate, getting mentally “stuck” on ideas or worries. Many with slow COMT describe an inability to shut their mind off, whether it’s replaying conversations, getting a song stuck in your head endlessly, fixating on to-do lists, or relentless self-critique.

Sleep Disturbances

Difficulty falling asleep despite exhaustion: You’re tired at night, but as soon as you attempt to go to sleep, your mind begins churning. That lingering dopamine and norepinephrine make it hard to downshift into sleep.

Light, fragmented sleep: Once you do sleep, it’s often not deep. You may wake up frequently—especially in the 2–4 A.M. window—sometimes with a surge of alertness or even panic for no obvious reason. Many slow COMT-ers report vivid dreams or nightmares and the sense that their sleep is “unrefreshing” even after a full night in bed.

Overreaction to sleep aids: In a cruel twist, the very supplements or medications meant to help sleep can misfire. Herbal sedatives might paradoxically wire you up. It’s not always the case, but sensitivity to sleep remedies is a common pattern.

Emotional Reactivity

Surges of anxiety or irritability: Small stressors can trigger big spikes in anxiety, panic, or anger. Your threshold for what constitutes “a big deal” is lowered, because physiologically your baseline adrenaline/dopamine is already high. Patients often say they snap or explode over minor issues and then feel bad about it.

Long recovery from stress: After an argument, social event, or stressful day, you might need hours (or even a day or two) to calm down. For example, one of my people with a slow COMT phenotype noted that even a call from his granddaughters left him wire and emotionally drained all evening. The stress break is lagged, so to speak, so emotions keep echoing long after the trigger is gone.

Mood swings: You may experience rapid shifts from anxious to depressed to calm and back again. Hormone changes, weather, or even blood sugar dips can agitate you. This can get misdiagnosed as bipolar or “just hormonal,” when in reality it’s the biochemical instability from slow COMT.

Supplement Sensitivities

Can’t tolerate B vitamins or methyl donors: Perhaps the hallmark of slow COMT individuals is feeling worse when taking methylated B12, methylfolate, or B-complex vitamins. Instead of more energy or better mood, these supplements might trigger anxiety, restlessness, or insomnia. This is because methyl B-vitamins ramp up the production of dopamine and other neurochemicals, which your sluggish COMT enzyme then struggles to clear.

Overreactive to adaptogens or “energy” supplements: Things like SAMe, certain herbal adaptogens (rhodiola, ashwagandha), or tyrosine can cause jitteriness or irritability. Even supplements that should be calming, like L-theanine or GABA, might have odd effects if not introduced carefully. It’s not that every slow COMTer reacts to every supplement—but there’s a notable pattern of needing tiny doses or very selective choices to avoid “paradoxical” reactions.

Preference for (or need to) avoid supplements altogether: Some people with slow COMT end up avoiding most supplements because they feel they “can’t handle” them. While understandable, this is usually because the right sequencing and dosages haven’t been found yet (you can read about that in my Roadmap). With a tailored plan, many slow COMT individuals can build tolerance to supplements that initially bothered them.

Hormonal & Estrogen-Related Symptoms

Hormone swings hit hard: Since COMT also helps break down estrogen, slow COMT—especially in women—can mean extra-intense PMS or perimenopausal symptoms. You might notice that anxiety, insomnia, or mood issues flare up at particular points in your cycle (PMS week, ovulation, postpartum, etc.). Physical PMS symptoms like breast tenderness, bloating, or headaches can be worse as well, due to higher levels of catechol-estrogens hanging around.

Histamine and estrogen tandem: Ever feel allergies or histamine intolerance get worse with hormone shifts? Histamine and estrogen can reinforce each other. Women with slow COMT sometimes report that they flush, itch, or get hives around hormone-change days. This is because COMT helps clear histamine’s cousin (norepinephrine) and certain estrogen byproducts; if those backlog, it may aggravate histamine pathways too.

Physical & Autonomic Symptoms

“On edge” body sensations: A slow COMT can leave your autonomic nervous system in a more activated state. You might experience heart palpitations or a racing heart from minor stressors or even when resting. Feeling a surge of adrenaline (that “drop” or flutter in your chest) over trivial things is common. Some also report sensations like internal tremors, tingling, or temperature swings (sudden flushing or chills) that correlate with stress or excitement.

Orthostatic intolerance: Lightheaded upon standing, especially in warm environments or after a hot shower, can happen because the adrenaline/noradrenaline spikes aren’t regulated normally. This overlaps with conditions like POTS (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome)—not to say slow COMT causes POTS, but it can contribute to feeling faint or dizzy when upright due to an overactive fight-or-flight response.

Exercise intolerance or post-exertional crashes: Paradoxically, while exercise is healthy, those with slow COMT might feel excessively wiped out from modest physical activity. For example, climbing a few flights of stairs or a short jog could leave you feeling shaky or overstimulated, then bone-tired shortly after. Overdoing it can lead to a “crash” the next day. This doesn’t mean avoid exercise altogether, but you will need to find a gentler, more gradual approach to fitness (we’ll discuss that in lifestyle strategies).

If several of the categories above resonate, there’s a good chance Slow COMT is a central player in your health picture. Slow COMT is routinely under-recognized in clinical settings precisely because it produces such a tapestry of symptoms that don’t fit neatly into one diagnosis.

Patients are frequently misdiagnosed with generalized anxiety, treatment-resistant depression, “adrenal fatigue,” or told their symptoms are just stress-related. Meanwhile, the underlying issue—a genetic bottleneck in catecholamine clearance—remains unaddressed. Recognizing the slow COMT pattern can be life-changing, because it allows targeted interventions that actually calm the storm rather than aggravate it.

How to Confirm a Slow COMT: Testing Your Genes (and Other Clues)

Genetic testing is the most straightforward way to get a reasonable idea of whether or not your have slow COMT. If you’ve done 23andMe, AncestryDNA, or another DNA test, you can get that analyzed for the main COMT SNP (or SNPs). The A/A (Met/Met) indicates the slow COMT variant on both copies of the gene (homozygous) and virtually guarantees a sluggish enzyme, though you can have slow COMT even without this.

Aside from DNA tests, clinical clues can very strongly suggest a slow COMT. One red flag is any negative reaction to methylation-support supplements—e.g. you felt awful after taking methylfolate or a B12 shot. That’s often a sign that your dopamine levels surged and your body struggled to compensate (a scenario highly suggestive of slow COMT). Likewise, feeling jittery or ill from popular “brain boosters” or pre-workout stimulants is another clue.

The more of the hallmark symptoms you have—across multiple domains (mood, sleep, hormone, sensitivities)—the more likely slow COMT is a factor.

For a definitive answer, though, genetic confirmation is useful. Many functional practitioners will specifically test COMT (sometimes via comprehensive nutrigenomic panels). If you haven’t been tested, consider doing a DNA test or a targeted SNP test for COMT. Knowing your genotype for the key SNP (A/A vs A/G vs G/G) can validate your self-observations and guide how aggressive or cautious to be with certain interventions.

Interpreting results: Again, Met/Met or “AA” likely means you’ve got a slow COMT.

Finally, it’s worth noting that COMT is not the only gene that influences these pathways. If you have a slow COMT plus certain other mutations (like in MAO-A, MAO-B, or DBH genes), the effects can be magnified. On the flip side, if you have slow COMT but also have fast MAO variants and/or DBH variants, that’s where things get a little more nuance. This is why a personalized approach is ideal: Your whole genetic and clinical context matters. Still, COMT status is a major piece of the puzzle that can explain long-standing quirks.

Supplements and Cofactors to Support a Slow COMT

There are absolutely targeted nutritional supports that can help “speed up” the COMT enzyme and stabilize your biochemistry. The key is to go about it methodically. Many well-intentioned people make things worse by jumping straight into high-dose methylation supplements (like methylfolate or SAMe)—which is precisely the wrong thing to do.

A slow COMT needs a foundation of minerals and gentle cofactor support first, then careful introduction of methyl donors. Below we’ll outline the most helpful supplements and cofactors, and how to approach them.

Targeted supplements can make an enormous difference for slow COMT, but choosing the right ones (and using the right doses at the right time) is crucial. Foundational nutrients like magnesium, along with careful methylation support, help “unclog” the COMT pathway.

SAM-e and Methylation Support: Provide Fuel CAREFULLY

SAMe (S-adenosylmethionine) is the primary methyl donor molecule that COMT uses as fuel. Without enough of it, even a normal COMT would slow down, and a genetically slow COMT gets even slower.

Therefore, increasing SAMe levels is central for optimizing a slow COMT.

You can raise SAMe indirectly by supporting your body’s methylation cycle. This means ensuring you have adequate methylfolate (active folate, e.g. 5-MTHF), methyl-B12 (methylcobalamin), B6 (as P5P), B2 (riboflavin), choline, zinc, trimethylglycine (TMG or betaine), etc. All these nutrients help your body convert homocysteine back into methionine, which then generates more SAMe.

But just keep in mind, these things usually make people with slow COMT feel worse if not done correctly. This is absolutely crucial: If you flood a slow COMT system with methyl donors too fast or incorrectly, you can get extremely unpleasant “overmethylation” reactions.

Overmethylation can feel like anxiety, irritability, insomnia, or even panic—essentially a temporary dopamine spike and imbalance. This is why we at MTHFRSolve generally do not recommend taking high-dose SAMe directly except in very specific cases.

Instead, start by gently improving methylation through diet (leafy greens for folate, proteins for B12 and methionine) and low-dose supplements if needed, and preferably one at a time. For example, you might begin with a low-dose methyl-B12 or a quarter of a B-complex, see how you react, then gradually build up. Some individuals with slow COMT find they tolerate hydroxy-B12 or adenosyl-B12 better at first (those are non-methyl forms of B12) and can later introduce methyl-B12 in small amounts. The same goes for folate: some do better starting with folinic acid (a precursor form) before jumping into full methylfolate – though others find methylfolate actually works better for them (it’s individual, as noted in one MTHFRSolve article on folate forms for COMT variants)mthfrsolve.com.

In practice, the goal is to gradually boost your SAM-e levels so that your COMT enzyme has plenty of the necessary fuel to work with. A properly fueled COMT can then better break down dopamine and estrogen at the right pace. The order in which you introduce methylation supports matters a lot (see my Roadmap). If you’ve felt worse on B vitamins before, don’t write them off entirely. It may be about how and when you take them.

Note: If all this talk of methylation is new to you, consider reading more on MTHFR (a related gene) and the methylation cycle. But even without deep biochemical knowledge, remember at the very least: Go low and slow with methyl donors (if you take any at all), and listen to your body’s feedback. If a supplement makes you jittery, back off and strengthen foundational supports first.

Magnesium: The Safest COMT-Supporting Supplement

If we had to pick a single supplement as a starting point for slow COMT, magnesium would be a top contender. Magnesium is an essential cofactor for hundreds of enzymes, and notably it is required for COMT to function properly. In fact, magnesium actually binds to the COMT enzyme and assists in the methylation reaction that breaks down catecholamines. Without enough magnesium, COMT can’t do its job efficiently—no matter what your genes are. And unfortunately, around half of people (at least) are subclinically magnesium-deficient.

For a slow COMT individual, magnesium supplementation is often hugely helpful. It helps in several ways: it directly supports COMT activity and indirectly helps stabilize the nervous system.

We generally recommends around 400 mg of magnesium per day at minimum for those with slow COMT, and often suggests even higher doses if tolerated.

The key is to choose the right form: avoid magnesium oxide, which is poorly absorbed and more likely to cause diarrhea. Better forms include magnesium glycinate, magnesium malate, magnesium threonate, or magnesium citrate (though citrate can be a bit laxative for some). Magnesium glycinate is a favorite for anxiety and sleep, as glycine is calming; magnesium threonate may better penetrate the brain; magnesium malate can help if muscle pain/fatigue is an issue (common in slow COMT folks who feel achy or tired). But these determinations are a little nuanced.

Start magnesium in the evening to aid sleep, or split dose morning and night. Many with slow COMT notice that after a week or two of consistent magnesium, they feel just a little bit less jittery and more resilient.

Also, magnesium helps other steps in the methylation and neurotransmitter pathway. For instance, it’s needed to make ATP (cellular energy) which powers SAMe generation, and it modulates NMDA receptors linked to glutamate (so it can reduce that overstimulated brain feeling). So, if you do nothing else, ensure you’re replete in magnesium.

(Note: Always check with your healthcare provider if you have kidney issues or other conditions before taking high-dose magnesium. But for most, it’s very safe.)

Lithium (Microdose): An Underrecognized Part of Fixing Slow COMT

When you hear “lithium,” you might think of high-dose pharmaceutical lithium for bipolar disorder. That’s not what we’re talking about here. We’re interested in micro-dose lithium, often in the form of lithium orotate or lithium aspartate supplements that provide a few milligrams of lithium (versus the 300+ mg doses in prescription form). Lithium, even at low doses, can be extremely helpful for slow COMT individuals.

How does lithium help?

Research and clinical observation show that lithium has neuroprotective and mood-stabilizing effects. Specifically for slow COMT, low-dose lithium can help regulate dopamine and glutamate levels. It’s thought to gently stabilize the neurotransmitter swings by promoting enzymes and pathways that decrease dopamine hyperactivity over time. Essentially, lithium can reduce the stress on COMT by preventing some of the excessive dopamine signaling upstream. Over the long term, this means your COMT isn’t countering giant spikes all the time, which can lead to a calmer baseline.

Additionally, many of us get far less lithium from our water and food today than our ancestors did. Lithium is a trace mineral naturally found in soil and groundwater. Modern filtered water and industrial farming have lowered lithium content in our diets. Some epidemiological studies even suggest areas with more lithium in water have better mental health outcomes. In essence, a little bit of lithium is part of human nutritional needs, and slow COMT folks may particularly benefit from topping it up.

Typical doses for nutritional lithium are around 1 to 5 mg per day. (For comparison, psychiatric lithium carbonate doses start around 300 mg—completely different scale.) You might find lithium orotate supplements in 5 mg capsules; some people start with half a tablet (~2.5 mg) to test tolerance. It’s generally well-tolerated at these low doses, but it’s wise to inform your healthcare provider especially if you have thyroid or kidney concerns (high-dose lithium can affect those, though micro-doses usually do not).

Always use reputable brands. Quality matters because lithium is powerful in excess. And never mega-dose lithium on your own—the goal is micro support, not pharmacologic effect.

Many patients report that after adding low-dose lithium, they feel more even, i.e. less brain chatter, slightly improved mood stability, and better stress tolerance. It’s not typically a dramatic overnight change; rather, lithium provides a gentler effect.

Other Key Cofactors & Aids: Potassium, Riboflavin, and More

Beyond magnesium and lithium, there are a few other nutrients to ensure are in place for optimal COMT function.

Potassium: Often overlooked, potassium works closely with magnesium in maintaining nerve function and cellular balance. There’s also some evidence that adequate potassium helps modulate adrenaline/noradrenaline release, which indirectly can relieve pressure on COMT (since less adrenaline needs clearing if you’re not over-releasing it). Make sure you’re eating potassium-rich foods like fruits (bananas, oranges), vegetables (avocado, sweet potato), and coconut water. Supplementing potassium isn’t usually necessary (and should be done cautiously, no more than 99 mg capsules unless under medical guidance), but do be mindful of getting enough in your diet.

Vitamin B6 (P5P): B6 is needed to synthesize neurotransmitters in the first place, and also to convert excess dopamine into downstream metabolites via other pathways. Ironically, too much B6 can cause issues (there’s a known phenomenon of B6 toxicity or high blood levels in some people even without massive supplementation—sometimes seen in slow COMT or related issues). The goal here isn’t to take high-dose B6, but to ensure you have enough active B6 (P5P form) to support overall neurotransmitter balance. A modest amount (like 1-2 mg of P5P) is usually plenty if needed. If you consume protein and a multivitamin you may already be sufficient. Monitor if supplementing—and note that unexplained very high B6 in blood tests can actually be another sign of sluggish metabolism in some pathways, interestingly (discussed in some of my other articles).

Zinc and Other Methylation Cofactors: Zinc, along with magnesium, is crucial for hundreds of enzymatic reactions. It helps with the creation of SAMe (through the methionine synthase step) and also in modulating NMDA receptors (glutamate balance). Ensure your zinc status is good (either through diet or a 10-15 mg supplement daily). Copper is a double-edged sword: you need some copper for dopamine-beta-hydroxylase (the enzyme that turns dopamine into norepinephrine), but too much copper can be overstimulating (and many multis have copper in them, which is discussed in “Why I Do NOT Recommend Multivitamins—The Case of Copper”). If you have slow COMT, you might want to avoid high-dose copper supplements or multis with copper unless a deficiency is confirmed, because copper can increase neurotransmitter production.

NAC (N-acetylcysteine): Worth mention, NAC is a supplement that increases glutathione (your body’s master antioxidant) and has multiple benefits for slow COMT situations. NAC can modulate glutamate and dopamine levels in the brain, helping to even out the neurotransmitter spikes. It also supports liver detoxification of various substances, lightening the load on COMT which also detoxes certain compounds. Clinical reports show NAC can reduce anxiety, obsessive thoughts, and even cravings (which align with slow COMT’s tendency toward OCD or addiction). Doses should be around 600-1200 mg once or twice a day. Some people feel a little more anxious with NAC initially (since it can mobilize toxins or affect glutamate transiently), but many tolerate it well. If sulfur intolerance is an issue for you (sulfur foods causing reactions), introduce NAC cautiously, as it’s sulfur-based.

The next section covers what not to do or what to be careful with, since avoiding the wrong supplements is as important as taking the right ones.

Supplements (and Foods) to Avoid or Use Cautiously with Slow COMT

Just as there are nutrients that help a slow COMT, there are also substances that hinder COMT or flood your system with more catecholamines—exactly what we don’t want when COMT function is already sluggish. Being aware of these can save you a lot of trial-and-error misery. Below are the top things to avoid (or at least moderate greatly) if you know you have a slow COMT variant:

Quercetin: A strong COMT inhibitor

Quercetin is a plant flavonoid found in many fruits and vegetables (onions, apples, berries, capers, etc.) that became popular as a supplement for its anti-inflammatory and antiviral properties. However, quercetin is also one of the most potent natural COMT inhibitors known. It actually binds to the COMT enzyme and slows it down. In someone with normal COMT, high doses of quercetin could potentially induce a temporary slow-COMT state; in someone who already has slow COMT genetically, quercetin can further worsen the enzyme’s activity.

Clinically, many of the slow COMT individuals coming through MTHFRSolve have been taking quercetin (especially daily or long-term), making them more anxious, irritable, or obsessive-compulsive—essentially exaggerating all the slow COMT traits.

Does this mean you can never eat foods high in quercetin if you have slow COMT? No. Food sources are fine. The amount of quercetin in even a quercetin-rich food (like red onion) is far lower than in a concentrated supplement capsule, and foods contain many other compounds that balance their effects. The issue is with high-dose quercetin supplements, or possibly super high consumption of quercetin-fortified products.

If you’ve been taking quercetin pills (common doses are 500mg to 1000mg), consider pausing them and see if your symptoms improve over weeks. For most slow COMTers, I recommend avoiding quercetin supplements altogether, unless there’s a special circumstance and you use it short-term (e.g. fighting a cold, and even then, there may be better options). If you do use quercetin for a specific reason, do so in moderation and for limited periods, always watching how it affects your mood and sleep.

EGCG (Green Tea Extract)

Green tea has many health benefits, but it carries a compound called EGCG (epigallocatechin gallate) which, like quercetin, can inhibit COMT enzyme activity. In fact, EGCG is often studied for this very property (it’s being looked at for prolonging certain neurotransmitters for cognitive benefit).

For a slow COMT individual, high amounts of green tea extract or very strong green tea could potentially make you feel more wired or tense. It’s tricky because green tea also contains L-theanine, which is calming; some slow COMT folks tolerate green tea in moderation (1 cup a day) because the theanine offsets some jitters. But excessive green tea or concentrated EGCG supplements are usually not a good idea—they can worsen the overload of neurotransmitters and estrogen.

If you love tea, you might switch to white tea or herbal teas for most of your cups, and keep green tea occasional. As for green tea extract pills (often sold for weight loss or antioxidants), it’s definitely best to skip those unless advised by a practitioner for a compelling reason.

Also keep in mind that matcha is a particular problem because it has particularly high amounts of EGCG. Probably best to avoid.

Rhodiola and Certain Adaptogenic Herbs: Proceed with Caution

Rhodiola rosea is an adaptogenic herb often touted to help with stress by modulating cortisol and neurotransmitters. However, rhodiola (and possibly a few other adaptogens) can inhibit enzymes similar to COMT or otherwise push neurotransmitter levels in a way that doesn’t interact well with slow COMT variants. It might give a short-term boost followed by a crash or agitation.

What about other adaptogens like ashwagandha, ginseng, maca, holy basil? Ashwagandha sometimes is better tolerated (it works more on GABA and cortisol), but some slow COMT individuals even find ashwagandha stimulating or “too much.” Ginseng (especially Panax ginseng) can raise dopamine and adrenaline—likely not ideal for slow COMT. Maca can have hormonal effects that might rev someone up slightly. Holy basil is more gentle and acts as a cortisol modulator—that one might be okay.

Ultimately: Approach stimulating herbs carefully. If something marketed as a “stress-reduction” or “energy” herb actually makes you feel on edge, it might be a mismatch for your genetics.

Caffeine (Especially Coffee): Handle with Care ☕️

Coffee is unfortunately a two-pronged threat to slow COMT. First, caffeine in coffee (and tea, soda, etc.) directly increases catecholamine release—it causes your adrenal glands to pump out adrenaline and noradrenaline and also prompts neurons to release more dopamine. That surge is what gives coffee its energizing kick. But in a slow COMT person, once those neurotransmitters are released, they stick around longer (since COMT is slow to clear them). So the “high” can turn into a prolonged jittery period and eventually a harder crash as your body finally clears the backlog.

Second, coffee contains metabolites like caffeic acid, which are natural COMT inhibitors.

In other words, coffee not only adds more stimulation, it also partially blocks the enzyme that would deal with that stimulation!

What to do if you love coffee or rely on caffeine? You don’t necessarily have to quit all caffeine (though some feel worlds better after doing so). Here are some tips:

Cut back to the minimal effective dose. For some, that means one small cup in the morning instead of three extra-large cups all day. See if you can gradually reduce your intake without withdrawal. Sometimes switching to green tea or oolong (lower caffeine + some theanine to smooth it out) is a gentler option. But recall green tea has EGCG; black tea might actually be a decent compromise (has caffeine but very little EGCG).

No caffeine on an empty stomach. This can blunt the jolt. Having some food in your system (especially protein or healthy fats) can slow the absorption and temper the adrenaline spike.

Cut off caffeine early in the day. Slow COMT folks often need a longer runway to clear stimulants. That 2pm coffee might still be influencing your receptors at midnight. Aim to have your last caffeinated beverage by late morning if possible, or go decaf in the afternoon.

Optimize other supports if you insist on caffeine. If you truly need that one cup to function, make sure you are diligent with your magnesium, electrolytes, and calming supplements to counteract it.

And remember, caffeine isn’t just coffee.

Watch out for hidden sources like energy drinks, pre-workout powders, certain sodas, and even chocolate (though chocolate’s caffeine is low, it has other stimulants like theobromine). If you’ve been a coffee addict, try a trial period off coffee (like 2-4 weeks) and see how your anxiety or sleep improve. If quitting is too hard, at least cut down and avoid using caffeine as a crutch for fatigue (that fatigue is there for a reason—your body likely needs rest, not a stimulant).

High-Dose Methyl Donors (Initially): Avoid “Methyl Overload”

We touched on this in the supplements section, but it bears repeating as an “avoidance” strategy: Do not jump straight into high-dose methylfolate, methyl B12, or SAMe when you identify a slow COMT. It’s a common mistake, because many internet sources (and even some well-meaning doctors) will see “slow COMT” and immediately throw on some methyl-folate and methyl-B12.

Avoid starting with: SAMe pills, high-dose methylfolate (e.g. over 200 mcg to 1mg to start) if you know they cause symptoms, high-dose TMG, and “methyl cocktail” supplement stacks that some companies sell (unless under guidance). Over time, you may incorporate some of these in controlled, small doses as needed—but not in the initial stage of a slow COMT protocol.

Alcohol and Nicotine: Briefly Noted

While not supplements, it’s worth noting two common substances:

Alcohol: Alcohol can feel like it calms you initially (it increases GABA and dopamine short-term), but it also raises adrenaline and disrupts sleep, and the aldehydes from alcohol metabolism can burden detox pathways that overlap with COMT’s work. Many slow COMT individuals find alcohol (especially excess) gives them disproportionate hangovers or anxiety flare-ups. Avoidance is prudent.

Nicotine: Some people self-medicate with nicotine (from vaping, smoking, or gum) for focus. Nicotine actually increases COMT activity transiently (interestingly), but it also releases a lot of adrenaline and dopamine. It’s not a healthy strategy for anyone long-term, and with slow COMT, the stimulant side can worsen anxiety and cardiac strain. If you use nicotine for cognitive help, consider weaning off or using alternatives (and certainly avoid combining it with high caffeine.

To sum up the avoidance list: anything that further inhibits COMT or excessively stimulates catecholamine release is counterproductive for slow COMT metabolisers. By cutting those out (or cutting down), you relieve a significant amount of pressure on your system. Many patients have noticed that just stopping a daily quercetin or mega B-complex, or quitting coffee, provided a noticeable reduction in anxiety or improved their sleep within days. These are low-hanging fruit—they cost almost nothing to implement and can make the rest of your healing roadmap much smoother.

(FAQ Spotlight: Do I need to avoid foods high in quercetin (like onions and apples) if I have slow COMT? No. Normal dietary amounts of quercetin in whole foods won’t significantly inhibit COMT. The concern is concentrated supplements or extracts.)

Lifestyle and Environmental Strategies for Slow COMT Support

While supplements and gene data are important, lifestyle changes are equally important in managing slow COMT. In fact, some of the most profound improvements come from non-pill interventions—adjusting how you live, work, and unwind to work with your nervous system rather than against it. Here we outline key lifestyle and environmental strategies:

1. Stress Management & Nervous System Resets

Chronic stress is the enemy of a slow COMT brain. If you have slow COMT, your body’s stress chemicals (adrenaline, cortisol, etc.) don’t shut off quickly, so it’s vital to proactively manage stress and give yourself frequent “resets.” Some tips:

Daily Relaxation Practice: Incorporate at least one intentional relaxation technique into each day. Great options are mindfulness meditation, deep breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, etc. These practices activate your parasympathetic nervous system, which can counterbalance the prolonged fight-or-flight state. Even 10 minutes of slow, deep breathing can signal your body to start metabolizing those stress catecholamines. Over time, regular meditation or breathing can actually lower your baseline anxiety and improve COMT function indirectly by reducing the constant flood of neurotransmitters to clean up.

Biofeedback or Heart Coherence Training: Devices or apps that teach you to modulate your heart rate variability (HRV) can be very effective. Slow COMT folks often have lower HRV (a sign the nervous system is stuck in overdrive). Practices from the HeartMath Institute or simple HRV biofeedback games help train you to find a calm state on demand. This can shorten the time it takes you to recover from stress or conflict.

Set Boundaries with Stimulation: This is a broad one. It means recognizing that your tolerance for stimulation (social, emotional, sensory) might be lower than others’. Give yourself space to take breaks during social events, to have quiet time each evening to unwind, and to design your schedule with recovery periods. For example, if you have a busy, people-filled day at work, consider a calm solo activity that night instead of more engagement. If loud noise and chaos trigger you, invest in things like noise-cancelling headphones, or practice politely excusing yourself when environments get overwhelming.

2. Sleep Hygiene & Circadian Alignment

Prioritizing good sleep is non-negotiable for someone with slow COMT issues. Since your natural inclination is towards insomnia or light sleep, you need to double-down on sleep hygiene:

Consistent Schedule: Go to bed and wake up at the same time each day, even on weekends if possible. A steady routine helps regulate your circadian rhythm. Your body clock will start to anticipate sleep at the right time, which can overcome some of that wired-at-night tendency.

Wind-Down Ritual: Implement a wind-down routine for at least 30-60 minutes before bed. That could include dimming the lights, gentle stretching, reading a (non-stressful) book, or taking a warm bath with Epsom salts (bonus: the magnesium from the salts can be calming). No screens for an hour before bed is ideal—blue light and information overload from phones/TV can spike dopamine and cortisol. If you must use devices, use blue light filters or glasses.

Optimize Sleep Environment: Make your bedroom as cool, dark, and quiet as possible. Consider blackout curtains and a white noise machine or fan to block noise. Some slow COMT individuals are so sensitive that even minor light or sounds disturb them. Also remove clutter or work-related items from the bedroom.

Natural Sunlight & Morning Routine: Interestingly, good sleep at night starts in the morning. Getting bright light exposure soon after waking (ideally sunlight outside for 10-15 minutes) helps anchor your circadian rhythm and increases daytime serotonin (which converts to melatonin later). Try to also do some gentle movement in the morning (walk, stretch); slow COMT metabolism can make it hard to wake up, but morning light and movement tell your body it’s time to be alert now—so it can wind down properly later at night.

Avoid Late Heavy Meals or Exercise: Eating a large meal right before bed or doing vigorous exercise at night can surge metabolism and adrenaline, keeping you awake. Aim to finish dinner at least 2-3 hours before bedtime. If you exercise in the evening, keep it moderate (like a relaxed walk or light yoga) rather than high intensity.

Despite best efforts, you might still have some sleep struggles (especially if hormones are fluctuating or stress is acute). In those times, implement natural sleep aids that are COMT-friendly: e.g., magnesium glycinate, L-theanine (from green tea, but in purified form it usually doesn’t have the EGCG issue and is quite calming), or herbal teas like chamomile, passionflower, and lemon balm. Just introduce one at a time to ensure you tolerate it.

3. Diet and Blood Sugar Balance

Some principles for slow COMT:

Maintain Steady Blood Sugar: Rapid swings in blood sugar (from skipping meals or eating high-sugar foods alone) can provoke adrenaline spikes—the body releases stress hormones when sugar crashes, which slow COMT folks then clear slowly, leading to prolonged jitters or sweats. To avoid this, eat balanced meals with protein, healthy fats, and complex carbs. Don’t go many hours on an empty stomach; some find 4-5 smaller meals or healthy snacks help keep things stable. Keep healthy snacks (nuts, Greek yogurt, hummus, etc.) on hand to prevent getting hangry (hungry-angry), which in a slow COMT person can spiral into anxiety. Prioritizing blood sugar stability is explicitly recommended: it gives your nervous system one less rollercoaster to deal with.

Adequate Protein, but Not Excessive Tyrosine in One Go: Protein is essential for providing amino acids for neurotransmitters. However, certain amino acids like tyrosine (the precursor to dopamine) in very large amounts might temporarily boost dopamine. This doesn’t mean avoid protein (not at all—you need it for overall health and even to produce SAMe), but be mindful of protein sources. If you find that a huge steak dinner activates you at night, it could be the tyrosine or phenylalanine load; you might do better with slightly smaller portions of protein spaced out. As a rule: protein in the morning and midday can fuel steady energy, whereas lighter protein at dinner (with more veggies) might aid sleep. Monitor how different foods feel for you.

Plenty of Vegetables & Fiber: A high intake of veggies not only provides vitamins and minerals (like the B vitamins and magnesium) but also fiber to help bind and excrete estrogen metabolites in the gut. Slow COMT leads to slower estrogen clearance; supporting elimination through regular bowel movements is key to avoid reabsorbing those estrogens. Aim for a variety of colorful vegetables daily, including cruciferous veggies (broccoli, cauliflower, kale) which support liver detox. Caution: while broccoli and such are healthy, don’t overdo concentrated forms like broccoli sprouts or sulforaphane supplements at first. Start with normal veggie servings.

Limit Junk and Stimulants: We talked about caffeine and alcohol. But also be wary of excess sugar, energy drinks, and MSG or other additives that can overstimulate some sensitive folks. A cleaner diet of whole foods can genuinely improve mental clarity and reduce anxiety. Some slow COMT individuals find that going gluten-free or dairy-free helps their inflammation or brain fog, especially if they have coexisting issues like autoimmune problems or gut dysbiosis, but that’s individual.

4. Hormonal and Environmental Toxin Management

Since slow COMT affects estrogen clearance, it’s wise to be proactive about minimizing excess estrogen and hormone disruptors:

Support Liver Detoxification: Your liver is the other major player (besides COMT) in estrogen and toxin clearance. Support it by eating those cruciferous veggies (which contain I3C/DIM naturally), getting enough protein (for glutathione production), and perhaps using gentle liver supports like milk thistle or dandelion root tea. Adequate B vitamins (especially B6, folate, B12, riboflavin) help liver enzyme function—another reason we eventually need those methylation cofactors.

Avoid Xenoestrogens: These are chemicals that mimic estrogen in the body and can add to the burden. Common ones include BPA (in plastics), phthalates (in artificial fragrances, vinyl, personal care products), and certain pesticides. Practical steps: use a water filter (to reduce chemicals and metals), store food in glass or stainless instead of plastic, choose natural or “free-and-clear” personal care items without synthetic fragrance, and consider eating organic for the “dirty dozen” high-pesticide produce. These steps reduce incoming toxins so your COMT and detox pathways have less to handle.

Moderate Phytoestrogens & Hormonal Supplements: Some natural products, like red clover, soy isoflavones, or even high-dose flaxseed, have phytoestrogenic activity. In moderation (like a serving of organic tofu or flax on your cereal) they’re usually fine and sometimes beneficial. But don’t go overboard with estrogenic herbs or supplements unless indicated, as you don’t want to add more estrogenic stimulation on top of what COMT is already struggling with. If you are on hormone therapy (like birth control or HRT), just be aware that slow COMT may cause you to have stronger reactions or side effects—work with a healthcare provider to adjust type or dose if needed.

Iron Levels: Iron deficiency (especially common in women) can actually exacerbate slow COMT symptoms through some mechanisms beyond the scope of this article. It’s worth getting your ferritin and iron levels checked. If you’re low, carefully restoring iron (slowly, and with guidance to avoid causing oxidative stress) could improve neurotransmitter balance. On the flip side, excessive iron is also bad (it can create oxidative stress), so aim for an optimal range, not too low or high.

5. Exercise

Because your recovery is slower, you want to avoid the trap of over-exercising and then crashing (physically and mentally). Here’s how to approach fitness:

Emphasize Low to Moderate Intensity: Activities like walking, light jogging, cycling at a comfortable pace, steady state cardio swimming, Pilates, or tai chi are excellent.

Interval Resting: If you do weight training or higher intensity intervals, build in longer rest periods between sets or sprints than a typical person might. This gives your system time to clear lactate and adrenaline. Pay attention to your heart rate; don’t be afraid to pause an extra minute if you feel your heart’s still pounding.

Recovery Days: Treat recovery as part of your workout program. You might do strength training one day, then the next day focus on stretching, a casual walk, or nothing strenuous at all. Over-training will backfire. Use tools like foam rolling, Epsom salt baths, or gentle stretching on off days to help muscles recover and to engage that parasympathetic (calming) response.

Timing: Some slow COMT individuals find that exercising later in the evening revs them up too much to sleep. If that’s you, aim for morning or afternoon workouts. Others actually sleep better with a bit of exercise after work because it releases stress. You have to experiment. Just avoid super intense things right before bed.

Before you go: If you have slow COMT, this 3-minute video could completely change how you understand your symptoms—and what to do about them.

In the following articles, I discuss in-depth what measures should be taken to help correct a Slow COMT variant:

Why I DO NOT Recommend Multivitamins—The Case of Copper — MTHFRSolve

What Supplements Should You Take if You Have a COMT Mutation? — MTHFRSolve

COMT and Protein — The Ultimate Guide to Optimizing Your Protein Intake for Your COMT Variant

Why Caffeine ☕ is Not for Everyone, Genetically Speaking — MTHFRSolve

A note from Dr. Malek:

If you’re interested in helping support my work, please consider sharing my website. You can link my blog posts on your social media pages, reddit forums, etc. It’s not easy competing with multimillion-dollar healthcare behemoths, so your help in amplifying a relatively small voice really goes a long way. Thank you :)

~Dr. Malek

Frequently Asked Questions about Slow COMT

Q1: “If I have the slow COMT gene, does that automatically mean I’ll have these symptoms?”

A: Not necessarily. As it’s commonly put: “Genetics load the gun, but environment pulls the trigger.” Many people have slow COMT variants but are asymptomatic, especially if they have a low-stress lifestyle, great diet, or other compensatory genes. Slow COMT creates a predisposition—a potential for higher dopamine/estrogen—but it often takes triggers like chronic stress, nutritional deficiencies, hormonal changes, or other genetic factors (like MAO or MTHFR variants) to manifest as overt symptoms. That said, even asymptomatic carriers might notice they feel better with some of these optimizations. It’s about understanding your tendencies. If you have slow COMT and feel fine, just keep an eye on things during life changes (like pregnancy, menopause, major stress, overtraining) when issues might pop up.

Q2: “I react badly to methyl B12 and methylfolate—does that mean I should never take them?”

A: It means you need to introduce them carefully if at all (and possibly address other issues first)—not that you can never have them. MOST slow COMT individuals indeed feel worse if they jump straight into high-dose methyl vitamins. Over time, as your body adjusts, you often can handle methylfolate and methyl B12 and benefit greatly from them. But not always.

Q3: “Do I need to get genetic testing to address this? Can I follow your roadmap based on symptoms alone?”

A: You can absolutely make many of these changes without genetic testing. The symptoms of slow COMT (and the responses to supplements) are often telling enough. If you strongly suspect slow COMT from the description in this article, you can proceed with the lifestyle adjustments and see if you improve. However, getting confirmation can be helpful, not just for COMT but to reveal other relevant genes. The knowledge can give you peace of mind and guide nuances (e.g., if you find you’re homozygous A/A vs heterozygous A/G, you might realize you need to be a bit more strict). Also, ruling out other genetic causes is useful—for instance, if your COMT was normal (G/G) but you have all these symptoms, it prompts looking at other causes (like high cortisol, chronic infections, or other gene variants). In short: testing is helpful but not mandatory to start making positive changes.

Q4: “What’s the difference between COMT and MTHFR? How do they interact?”

A: COMT and MTHFR are two different genes in the methylation and detox orchestra. MTHFR is an enzyme that helps produce methylfolate, a form of folate needed for overall methylation (including making SAMe). COMT uses those methyl groups (like from SAMe) to detox catecholamines. An MTHFR mutation (like C677T) can reduce your methylfolate production by some percentage, which could lower SAMe levels somewhat, thus slowing COMT activity further (due to cofactor shortage). The important interaction is: if you have both, you must address methylation support carefully. Often treating the MTHFR (with low-dose folate/B12) will help COMT by raising SAMe, but it’s a balancing act to not overshoot. This is where individualized plans or working with a knowledgeable practitioner helps, because it can get complex. But many people successfully manage having both variants.

Q5: “Is slow COMT ever beneficial? It feels like a curse.”

A: It can feel like a burden when you’re dealing with anxiety and insomnia, yes. But believe it or not, there are some potential advantages (and evolutionary reasons this gene persists). People with slow COMT (Met/Met) often have better memory and attention to detail—your brain hanging onto dopamine longer can enhance certain cognitive functions, especially in calm conditions. You might find you excel in tasks requiring focus and analysis (until you get overstressed). Slow COMT individuals can also be very passionate, persistent, and sensitive in a positive way—you might experience music, art, or emotions more deeply (because you literally feel more due to those neurochemicals). In contrast, fast COMT folks (Val/Val) may be more go-with-the-flow and less anxious, but they can miss details or lack some of that depth. In short, “worrier” can also mean “warrior” in certain contexts: if you harness it, that vigilant mind can be an asset (think of professions like surgeons, air-traffic controllers, or scholars—a bit of extra baseline adrenaline can drive excellence under pressure, as long as it’s managed). The goal of this roadmap is to mitigate the downsides (excess anxiety, etc.) so that you can capitalize on the upsides of your genetic makeup. Many people find that once they balance their slow COMT, they have the best of both worlds: mental sharpness and emotional calm.

Q6: “Can I ever drink coffee or green tea again? Must I avoid them forever?”

A: It depends on your individual tolerance and how well-controlled your COMT is after implementing changes. Many slow COMT individuals find that once they address the root causes (with magnesium, etc.), their tolerance for occasional caffeine improves. You might be able to enjoy a small cup of coffee on a lazy Sunday with no ill effect, whereas before it would’ve wrecked you. The key is moderation and timing. As for green tea, a cup a day is often fine especially if it’s not ultra-strong—and it has L-theanine which helps. Just be cautious with concentrated forms (matcha lattes can be quite high in EGCG and caffeine, for instance). A trick some people use is taking a small dose of L-theanine or extra magnesium when they have caffeine, to blunt the jitters. Ultimately, as your system stabilizes, you might experiment with reintroducing these in small amounts and see. If the answer turns out to be “no, even a little makes me feel bad,” then it’s a personal choice: you may decide the momentary pleasure isn’t worth it.

Q7: “I have slow COMT and my friend has fast COMT. Can we follow the same diet and supplement plan?”

A: Not exactly. There will be some divergence in approach. A fast COMT (Val/Val) friend might actually need opposite strategies in some areas: for example, they might benefit from a bit more caffeine or green tea (since they clear things fast), or they might handle methyl B’s without issue and actually need higher doses to get an effect. They may struggle more with focus and motivation, so things like tyrosine supplements or higher protein diets (for dopamine) might help them—whereas those could overwhelm a slow COMT person. If you both take a basic multivitamin and eat a generally healthy diet, that’s fine, but when it comes to augmenting brain chemistry, personalization is key. Fast COMT folks more rarely have the “methyl donor sensitivity” issue, so they can follow a lot of standard health advice without trouble. If you’re the slow COMT, you’re the one who has to zig where others zag occasionally. The encouraging part is that by taking care of your specific needs, you’ll likely end up feeling better than many people who never consider their genetics at all.

Q8: “Will supporting my slow COMT also help with other conditions like OCD, ADHD, or anxiety disorder?”

A: It certainly can. Slow COMT is strongly linked with traits of OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder), addiction, anxiety, and even certain types of ADHD (especially the inattentive type where the person is spacey until pressure hits, then they hyperfocus). By optimizing COMT, you’re addressing a root contributor to those issues. Many people see their formal diagnoses or symptom severity improve: e.g., an individual with OCD tendencies might find their intrusive thoughts diminish when using magnesium, NAC, and avoiding COMT inhibitors. Someone with general anxiety might realize they were just undermethylated or over-catecholaminergic, and now with the protocol they feel much calmer (perhaps negating the need for an SSRI or benzodiazepine medication). That said, these conditions are complex and can have multiple causes. COMT is one piece. If someone has severe ADHD, they might still benefit from medication or other interventions—but understanding their COMT status could, for instance, explain why they had side effects to stimulants or guide them to non-stimulant options.